The Despair of Jeff VanderMeer (And the Things We Become)

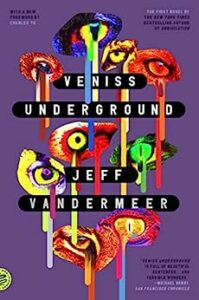

Veniss Underground

Jeff VanderMeer

Hardback / Ebook

ISBN: 978-1250860958

Picador Paper, April 2023, 336 pages

I am now an essayist. This statement became true just now, as the first of you set eyes on these words, and with every word you read, I continue the clumsy process of becoming something new. We shed. We pick up.

I am now an essayist. This statement became true just now, as the first of you set eyes on these words, and with every word you read, I continue the clumsy process of becoming something new. We shed. We pick up.

• • • •

Jeff VanderMeer’s characters are often in states of transformation. Sometimes these states are literal, as with the slow genetic warp of the protagonist, Ghost Bird, in Annihilation. Or the fluid imitations of the childlike plant in Borne. Or the horrific Living Art of Quin in Veniss Underground. Or the sickly violation of a person transformed into a strange bird, then into a garment worn by an antagonist. (If you haven’t read VanderMeer’s haunting novella, Strange Bird, I highly recommend it.) Other times, these transformations are both literal and figurative. Consider Salvador, the genetically engineered meerkat in Veniss Underground, who (in the literal sense) transforms from a physical threat to a dismembered guide while figuratively changing (in the eyes of Shadrach, the protagonist) from a soulless machine to a sentient being. In Bliss—a story rooted in grim reality—a wayward trio is broken apart, and one frustrated soul is reduced to nothing more than blood on the walls of a vacant room. For the remaining duo (who never had an opportunity to see the body), this character becomes a phantom. Dead, but not. Gone, but somehow present. Forever lingering in the quiet, mournful recesses of their minds.

• • • •

VanderMeer’s transformations can be weird, thrilling, grotesque, or transcendent. Often, an unsettling mix. But for all of the spellbinding physical changes endured by VanderMeer’s characters, it’s the depictions of their shifting relationships that grip me.

• • • •

In Borne, the titular creature—a mimic—falls into the hands of two post-apocalyptic scroungers. First viewed as an atrocity, Borne is later embraced as a child by half of the dysfunctional couple. But Borne isn’t the child they need. And they are not the parents Borne needs. As is so common in families, they fail each other. The child flees in the aftermath, and, as time passes, becomes many things.

• • • •

And the mother—upon a late reunion—laments the loss of the thing as she knew it.

• • • •

Veniss Underground features three protagonists. A chain of fools. I describe them as such with deep—embarrassingly earned—empathy. The first link on the chain is Nicholas, a struggling artist who seeks to elevate himself and meets a horrific fate due to his desperation and ego. He loses himself, over and over again, as “the skin comes off and the skin goes on, like a suit.” This description given by Nicholas—though shockingly literal—easily fits many a lost soul that scrambles for identity.

The second link on the chain is his well-to-do twin sister, Nicola. She pursues Nicholas, though they’ve grown estranged. And that’s her mistake. Early in the novel, Nicola wistfully describes her relationship with her brother as “two as one.” But the child she knew was gone (and had been) well before Nicholas disappeared. Nicola had grown into something far different than the child she’d been. Nicola pursues the shadow of the sibling from her youth and, just like Nicholas, loses herself in the process.

Completing the chain is Shadrach, Nicola’s former lover, who she had shunned long ago. Shadrach aims to save the love of his life, but this version of Nicola no longer cares for him and will not again. So Shadrach searches and suffers. He needn’t have. These three could have been spared immense pain if they’d accepted that the people they’d known had grown into strangers.

• • • •

In Bliss, a trio of musicians clings to the solid unit they once were, even after their star has faded and their relationship has become fraught. Their journey to reclaim their glory claims one of their lives, that of the member the others had outgrown. All three could have lived—and been spared incredible trauma—if they’d simply let go of the past. But they could no more do that than Oedipus could be swayed from his course with Jocasta. The story, its horrors, and its beauties depend on the fall.

• • • •

Of VanderMeer’s tragic figures, it’s Annihilation’s protagonist, Ghost Bird, that I connect with most intimately. Perhaps because her account was written in the first person, for which, as a reader, I have a particular fondness. More likely, I recognize the flawed way she invests in minutiae as opposed to those around her. She values the intricate biome of a puddle more than the puzzle of her husband’s wants and needs. Upon realizing this mistake, she sets out to correct it. But in the sad race between realization and consequence, as is often the case, the latter has already won. And those consequences haunt Ghost Bird, as they haunt me, and perhaps you.

• • • •

Again and again, VanderMeer’s characters fail to be the person their family needs, just as their families fail them. Their journeys are penitent marches into past follies that cannot be undone.

• • • •

But with the exact mechanism that VanderMeer uses to elicit despair, he inspires hope. As frightening as transformations can be, they’re nothing compared to the hidden harm of remaining the same. Of mistaking atrophy for comfort. Or intransigence for virtue. As Ghost Bird follows in the footsteps of her lost husband, she faces (calmly, gracefully) something that conjures profound dread in the best of us: inevitable—unknowable—change.

• • • •

Ghost Bird accepts that change. And though she suspects her lover may never be found, she still hopes to glimpse him: “In the eye of a dolphin, in the touch of an uprising moss, anywhere and everywhere.” She embraces the final transformation we endure, from self to memory. And how—as memories—we inhabit all the places our loved ones dare to hope. Even as we linger, unbidden and unwanted, in the corners of their regrets.