Time to Burn Down Hell House

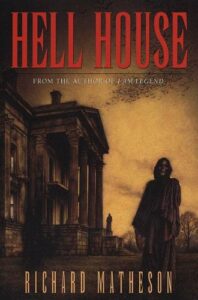

Hell House

Richard Matheson

Ebook edition:

ISBN: 9781429913645

Tor Books, April 2011

Originally published 1971, Viking

Richard Matheson’s 1971 horror classic Hell House is a much-mentioned and venerated cornerstone of the genre’s most beloved trope: the haunted house. A retread on the 1959 progenitrix of the haunted house novel, The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson, Matheson’s entry into the canon dares to ask the question: what if a haunted house was for MEN? It asks this with the same ferocity as an ad for Dude Wipes or a strenuously heterosexual yogurt brand, and it answers its own question with a bellowing cry of SHOW US YER TITS. This book is a laughably paranoid unscary exploration of things that go bump in the night, but when you run the machine that’s built to translate ghost noises, it turns out bump means my boner is sad and it’s all your fault.

Richard Matheson’s 1971 horror classic Hell House is a much-mentioned and venerated cornerstone of the genre’s most beloved trope: the haunted house. A retread on the 1959 progenitrix of the haunted house novel, The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson, Matheson’s entry into the canon dares to ask the question: what if a haunted house was for MEN? It asks this with the same ferocity as an ad for Dude Wipes or a strenuously heterosexual yogurt brand, and it answers its own question with a bellowing cry of SHOW US YER TITS. This book is a laughably paranoid unscary exploration of things that go bump in the night, but when you run the machine that’s built to translate ghost noises, it turns out bump means my boner is sad and it’s all your fault.

But why bother pointing out the myriad failures of a half-century old novel? Matheson is dead, but like Hell House’s moldering emasculated patriarch Emeric Belasco, he haunts us still. With a lingering nostalgia unmoved by decades of new and exciting work, many horror publications and fans insist that the genre’s golden age rests squarely in the lap of about four white men who wrote most of their best work between 1970 and 1985, when men were men and zombies weren’t played out yet. Even now, magazines like Paste (bit.ly/3IZqIp7) and Nightmare (bit.ly/3IXqYoL) and websites like Unbound Worlds (bit.ly/3Z7SPbv) and Barnes and Noble (bit.ly/3xV4Vc5) count Hell House as one of the greatest, the scariest, the most important horror novels of all time. And of course, the reigning master of horror, Stephen King (long live the king) gave this book a blurb that cannot be denied, even across five decades: “Hell House is the scariest haunted house novel ever written. It looms over the rest the way the mountains loom over the foothills.”

No one escapes Hell House. It’s a juggernaut of the genre, and anyone discovering a new penchant for horror will be borne ceaselessly back into it. I read this book for the first time when I was getting into horror and someone told me I had to; I must have been about ten or eleven years old. I read it again, as a teenager and as an adult, and it only becomes weaker and more laughable each time. Someone has got to warn first-timers not to go in there. Someone has got to tell them what they’re getting into.

Here’s the pitch: Physicist Lionel Barrett takes two mediums into the Mt. Everest of haunted houses to produce proof of life after death for dying billionaire Rolf Rudolph Deutsch. Lionel is an impotent cynic, his wife is a repressed lesbian, one of the mediums is hot and the other one has boundaries. The house reveals its secrets to this group with all the subtlety of a subway flasher: evil short guy Emeric Belasco started the party to end all parties, bringing people to his house for sex, drugs, and cannibal debauchery that eventually led to the greatest of all horrors: the breakdown of a social order that had previously held someone responsible for washing the sheets.

Matheson ties himself in knots trying to dream up the most depraved ways that a group of people might have profaned a space until it could never be clean again. The mantels have porn carved into them. The chapel features a carved statue of Jesus hung on the cross, but also enormously hung. Ghosts immediately manifest in the form of sexual assault against the party of investigators . . . but only the women. The hot medium, Florence Tanner, is made to strip naked and spread ’em to prove she’s not faking any of the spooky stuff that happens. This display excites the bejesus out of Lionel’s wife Edith, who is repressing some serious sapphic desires, but also the ghost who gets an ectoplasmic eyeful. Bored conversations between unmolested men reveal that Belasco’s guests were sequestered long enough to get pregnant and dispose of either aborted fetal tissue or murdered infants (the text, predating Roe vs. Wade by two whole years, is too delicate to say what it means this time and only this time) into a sort of moat around the house, a body of water thereafter referred to as “Bastard Bog.”

This delicacy is riotously funny, considering Matheson spends great volumes of ink writing out how the ghosts bite the hot medium on her big luscious full breasts, how the assault mats with blood her coppery pubes, how she feels a ghostly erection deep within her rectum, how she craves the unnatural embrace of the other woman, Edith, and senses their mutual attraction.

The other funny thing here is that Florence the hot medium is expressly not a physical medium. She’s a spiritual medium, working through a breathtakingly racist spirit guide who speaks like an Italian bit actor playing a Native American in a John Wayne movie. The physical medium is this other guy, Fisher. Fisher’s masculine powers of aloofness and control keep the ghosts out of his rectum, which would just be icky if it happened to a man. The venal vulgarity of the house is visited only on the women in the party, including one unforgettable scene in which a possessed Edith is enraged that her husband will not rise to the occasion and yells at him; “Never had a tit before? Try it! It’s delicious.”

Clownery aside, Hell House is a foundational text for only one discernible reason. It sets the blueprint for possession and haunting novels over the second half of the twentieth century where all perversion and desecration and contamination that any diabolical entity can muster will be visited and made evident in and on the body of a woman or a girl. This whole genre is written on the backs of women, even as it demonizes female sexuality. Who gets possessed? Who gets raped by ghosts and demons and bad guys? Who gets punished for having sex? Who is made into the physical proof of the existence of the beyond through violations unimaginable to the heroes of these books; men routinely murdered but never violated by anything other than blade or bullet or bite?

Women.

Richard Matheson’s Hell House is written in terror of, with disrespect for, without empathy for, with animosity towards, with no hint of their own motivation, without any clue how to relate to . . . women. Its staying power as a classic of the genre today is as baffling as the book’s dedication: with love, for my daughters Bettina and Alison who have haunted my life so sweetly.